Your Lips Move, but I Can't Hear What You're Saying

“The erroneous theory is: to speak is to understand. Tell that to Stephen Hawking,”

Take a moment to say this sentence aloud. “The bird is blue.” Effortless, right? Now, humor me here, touch your tongue to the roof of your mouth and don’t move it. Try saying the sentence again. It may sound something like, “Du ber issh bu.” Still somewhat intelligible? Do you think someone would know what you were saying? Ok, last one. This time close your mouth. Don’t move your jaw, lips, or tongue. “Mmm ggg ii ggg.” At this point you may be amused (or irritated) by this exercise.

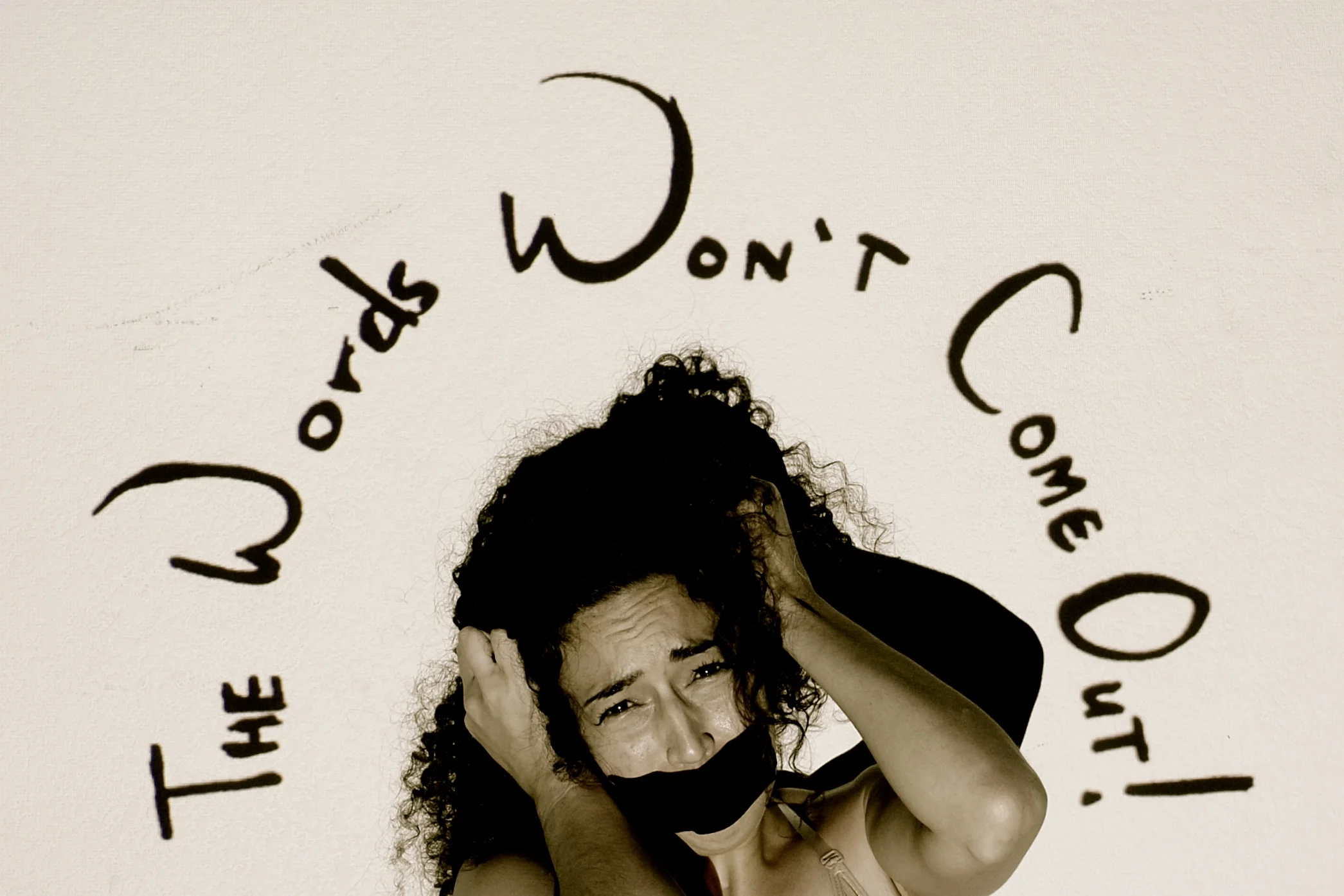

For a moment, try to imagine what it would be like to not be able to articulate a thought. “The bird is blue,” you say in your mind, but when you send the command to your mouth, it has no intentions of complying with your request. Replace that innocuous statement with something more poignant like, “I’m hungry.” Or, “The secret of the universe is....” Or perhaps even more disconcerting, “Help me!”

We rarely take a moment to realize just how incredibly intricate and profound the act of speaking really is. You have a thought. Then you move your lips, tongue, jaw, and vocal chords while still maintaining a consistent breath with the correct intonations. Once the noises are coming out of your body, you are able to identify that that is you speaking. Then, as if through magic, a person listening (after equally amazing neuronal processing) has that thought or at least a version of it in their mind. Amazing!

Speech is one of the quickest and most efficient methods of communication. However, communication is not synonymous with speech. (If you’ve ever watched a U.S. political debate you know the extent someone can produce speech but not communicate a thought!) We all know someone who talks endlessly, but never communicates a thing. As a spoken language driven species, we associate intelligence with one’s ability to convey a thought, typically through speech. We put such a strong emphasis on speech that we tend to assume if someone does not or cannot speak, there is some sort a cognitive disability as opposed to some sort of motor or expressive disability, such as in the case of those who have had a stroke or a developmental disorder. With anyone who has limited communication, it is imperative to assume intelligence… Assuming the alternative could be detrimental to an already seemingly hopeless and isolated situation. Try to imagine the level of frustration and isolation you would feel if you had something to say but couldn’t find your voice.

I work with a little girl on the autism spectrum and have seen the desperation in her face when the words won’t come out. I know she is in there. I know there is a voice in her. I know that just because she does not talk, does not mean that she does not have thoughts. There are some incredible individuals locked in their bodies that have managed to find their voices and change our perception on these silent souls. The locked-in patient and author of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Jean-Dominique Baub, the non-verbal published authors with autism Ido Kedar, Tito Mukhopadhyay, Elizabeth Bonker, and Carly Fleischmann, and the cosmically renowned, ALS afflicted Steven Hawkins.

Imagine what we would be missing out on had we continued to assumed “the erroneous theory… to speak is to understand” as the thirteen-year-old Ido Kedar points out in his profoundly insightful book. Imagine how much more we will know as we develop ways to help these individuals communicate and find their voice.

Always assume intelligence.

Us believing they can is half the battle for them.

Readings:

Ido In Autismland: Climbing Out of Autism’s Silent Prison by Ido Kedar

I Am In Here by Gennie Breen and Elizabeth Bonker

How Can I Talk If My Lips Don’t Move by Tito Mukhopadhyay

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Baub

Carly’s Voice by Arthur Fleischmann and Carly Fleischmann

“The truth is that much of what people say is meaningless. They instantly say what comes into their head. Their lack of working on their thoughts makes their thoughts unfocused. It’s not only a curse to be quiet, it’s a blessing of thinking inside and saying what is important, so a bad thing may be an opportunity too.”

Originally published in United Academics Magazine